The aesthetic politics of graffiti removal in Contemporary São Paulo

In this commentary, postdoctoral researcher Nate Millington comments on the aesthetic politics of Graffiti removal in São Paulo.

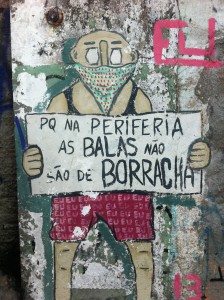

Memorial to those killed by police violence in Brazil and the United States: “They couldn’t breathe.”

In his first few weeks in office, the newly elected mayor of São Paulo—Jõao Doria, a businessman and reality tv star whose election was primarily a rebuke of the city’s rare flirtation with governance by the Worker’s Party—has spent considerable energy painting over graffiti in the city in the service of what he calls a ‘beautiful city.’ This represents a dangerous moment for those interested in urban life and its virtues and for those who celebrate the capacity of the city to give space to those who seek alternative lives. It is one more instance of the crude reshuffling of the visual, sensorial landscape in favor of one more conducive to global grade and elite forms of aesthetic appreciation.

To be sure, Doria’s attempt to clean up the city is one instance in a longer history of the policing of certain kinds of expression. Beset for years by graffiti as well as pixação—a type of tagging specific to Brazil—leaders of São Paulo have long attempted to cohere its landscape through the development of initiatives designed to curb visual disorder. The most notable of these is 2006’s Cidade Limpa [Clean City] law, which outlaws graffiti as well as outdoor advertisements and billboards. Profiled in the 2013 documentary Cidade Cinza [Grey City], the Clean City law attempts to substitute the disordered aesthetics of contestation represented by graffiti for the orderly landscape of grey that marks the city’s monochromatic landscape. Successful in limiting outdoor advertisement, the city has been far less successful in preventing young people from writing on the city’s walls.

Of course, as Marcio Siwi has pointed out, a distinction needs to be made between what is referred to as graffiti and its “angry cousin,” pixação. Graffiti refers to what is increasingly called street art, whereas pixação refers instead to a form of aggressive tagging with a very specific visual language. Those who engage in pixação (often referred to as pixadores) often compete to paint in the most dramatic landscapes possible. In recent years, graffiti or street art has reached levels of acceptance by the art world that allows it to be seen as more than just vandalism. Pixação, on the other hand, lacks this level of acceptability, and is often articulated through the lens of vandalism and criminality.

Of course, as Marcio Siwi has pointed out, a distinction needs to be made between what is referred to as graffiti and its “angry cousin,” pixação. Graffiti refers to what is increasingly called street art, whereas pixação refers instead to a form of aggressive tagging with a very specific visual language. Those who engage in pixação (often referred to as pixadores) often compete to paint in the most dramatic landscapes possible. In recent years, graffiti or street art has reached levels of acceptance by the art world that allows it to be seen as more than just vandalism. Pixação, on the other hand, lacks this level of acceptability, and is often articulated through the lens of vandalism and criminality.

The distinction made between graffiti and pixação is linked to the fact that cities around the world increasingly employ street art as a form of urban beautification, a way to regenerate purportedly declining neighborhoods and generate central city reinvestment and raise property values. This has created a specific link between processes of gentrification and the funding of street art. This means that narratives about street art’s capacity to give voice to oppositional politics can often be overstated. At the same time, the persistence of graffiti and tagging can still function as a reminder of those who are left out of urban visibility. Both pixação and graffiti are claims made on the city’s landscape, forms of intervening into the complex and often unequal dynamics of the contemporary city. They are, in the words of Teresa Caldeira, forms of “imprinting” on the urban landscape. From Style Wars to Cidade Cinza, the act of writing on public walls tells a consistent story in the global urban landscape: of those excluded from the formal political life of the city, who choose to make themselves known in contentious ways.

What is interesting about Doria’s anti-graffiti politics is that his Beautiful City plan focuses not just on pixação, long a target of municipal authorities, but also on more valorized forms of graffiti or street art. Recent videos shot by residents of the city have highlighted the targeting of by now iconic instances of graffiti in the city, even as he has stated that some works will be allowed to stay. In response to outcry from residents, Doria has recently suggested that he will repaint some of the murals that were removed. It remains to be seen how this process will go, or what artists will be asked to participate.

Of interest here, and it is interest provoked by the film Cidade Cinza as well, is the way in which the act of painting over is also an act of determining artistic merit. In one of the scenes in Cidade Cinza, municipal workers debate which piece of wall art is art, and which is just graffiti. While perhaps a commonsensical distinction—presumably we can all tell tagging from the more refined project of street art—it is nevertheless a question that empowers unexpected people to become a type of art critic, whether they are low-paid municipal workers or highly-paid businessmen turned mayors. Where is the line between art and graffiti, and who should be empowered to police it?

More expansively though, the ongoing painting over of graffiti reveals much about the contemporary politics in São Paulo, the move away from a technocratic left government represented by the previous mayor Fernando Haddad to a type of visual politics represented by Doria’s insistence on a clean, palatable landscape. The painting over of graffiti is matched by ongoing efforts to police spontaneous public space and carnival blocos on behalf of the Doria administration, and is one more form through which São Paulo’s long-standing dynamics of resistance and occupation are being challenged in the sphere of aesthetic politics. In addition to the broader dynamics of austerity and privatization that are marking the political turn in São Paulo (and beyond), Doria’s politics render aesthetics into the mundane canvas of elite respectability. Graffiti removal is the visual corollary to Doria’s anti-poor politics and the move away from efforts to make the city’s landscape more egalitarian.

Those who know me know that my love for São Paulo runs deep, a fact that complicates my capacity to write about the city in a detached way. As I write in my dissertation, São Paulo is a city of undeniable cultural vitality where contestations over the fabric of the city are commonplace. It is a sprawling, complex metropolis, the economic heart of Latin America, and a site of incredible wealth that is bisected by a brutal delineation between center and periphery. It is a city of immigrants and migrants, a place of opportunity and extreme hardship, a famous “city of walls” to reference Teresa Caldeira again. It is a deeply queer city in a country that murders LGBTQ people at appallingly high rates, a working-class city, a global city, a city of ostentatious wealth, a city of fortified enclaves and armored cars, a city with the highest rate of personal helicopter ownership in the world. It is a city of astounding cultural vitality as well as a center of global financial capitalism and brutal inequality.

Those who know me know that my love for São Paulo runs deep, a fact that complicates my capacity to write about the city in a detached way. As I write in my dissertation, São Paulo is a city of undeniable cultural vitality where contestations over the fabric of the city are commonplace. It is a sprawling, complex metropolis, the economic heart of Latin America, and a site of incredible wealth that is bisected by a brutal delineation between center and periphery. It is a city of immigrants and migrants, a place of opportunity and extreme hardship, a famous “city of walls” to reference Teresa Caldeira again. It is a deeply queer city in a country that murders LGBTQ people at appallingly high rates, a working-class city, a global city, a city of ostentatious wealth, a city of fortified enclaves and armored cars, a city with the highest rate of personal helicopter ownership in the world. It is a city of astounding cultural vitality as well as a center of global financial capitalism and brutal inequality.

At times these dynamics overlap productively, and at times not. The queer energy that permeates the city’s center—where decades of outmigration have yielded a space that retains a working-class energy in spite of it all—is not matched by those who experience the city through the windows of armored cars, who celebrate the aggressive and murderous policing of black and brown residents, who celebrate reductive and bland culture over the city’s vital creative spaces. This can be seen in the ongoing proliferation of peripheral cultural production, whether seen through figures like the brilliant rapper Emicida or more high-concept theater and art produced by collectives scattered throughout the city (of which one example is Estopô Balaio, a theater group active in the neighborhood of Jardim Romano in the city’s eastern edge).

Painting over graffiti is one instance of a broader assault on the vitality of urban life in São Paulo. To be sure, aesthetic tastes are multi-faceted and dynamic, and to reduce the city’s complex culture to a story of out-of-touch elites is of course reductive. But if the events of the last 12 months have made anything clear, it is that the task of finding ways to live together across difference is the project going forward. Painting over graffiti is one more small-scale assault on our collective lives, our capacity to take seriously the freedom the city offers. The dynamics of graffiti pale in comparison to the ongoing reshuffling of the city’s broader political life, but they suggest a visual accompaniment to processes of austerity and fortification that are currently remaking the city. In a city with an estimated housing shortage of 230,000 units and a mayor who seems both uninterested in the city’s expansive periphery and its vital center, efforts to police the city’s creative landscape take on an added weight. What is at stake in the painting over of graffiti in the city is not just that the city’s visual language will be changed, or that famous pieces of art will disappear. That is, to be sure, a loss. But what Doria represents is the increasingly hostile assault on what it means to live together by those seemingly disinterested in that project.

Doria’s assault on street art is one more attack on the vitality of what it means to live together, another embarrassing capitulation to those who value order over engagement, another reactionary turn in a moment full of them. The stakes now are too high to take any of this lightly.