Jonathan Silver reflects on the recent water shut offs in Detroit

A police car moves toward water shut off protesters in Detroit

(Picture: Detroit Water Brigade – https://twitter.com/DETWaterBrigade)

You might have seen images circulating out of Detroit over the last few weeks of the unfolding humanitarian crisis. Utility company vehicles, highly weaponized police, distressed but resisting residents (often it seems from the African American community), warnings and condemnations from civil society and from the UN and the act of disconnection to that most basic of human rights, water. We’ve certainly become familiar with such images for many years now but we’ve fixed these moments in the grand neoliberal experiment in the African cities of countries such as South Africa and Nigeria (and of course the wider global South). This time though our maps of the cities of the world have been fractured, turned upside down even. For we have to leave those African neighbourhoods and cities from which we have become accustomed to seeing an ongoing war against the urban poor through controlling access to urban infrastructure services. Instead we have to take a step back into the ‘heart of empire’ to locate these moments of infrastructural conflict that challenge how we categorize and place cities across the globe.

Since last summer over 42,000 disconnections to Detroit’s water system have taken place, concentrated in poor and African American communities of the cities devastated neighbourhoods, with these actions being processed on debts as low as $150 or two months non-payment. But despite the 15 day halt announced this week this might be only the start of what is viewed by the Detroit Water Brigade as a systemic campaign to stop water flowing to around 40% of the cities population over the coming months. The consequences of these disconnections are almost unimaginable for residents left without the ability to clean, to cook or to drink, with National Nurses United calling for an immediate halting of the shut offs before a significant public health crisis is created. Parts of the local establishment have even turned against this mass shut off, warning not just of the cost to historically disadvantaged parts of the city but the city’s image in the wider world. Yet in the build up to privitisation of the water system in Detroit maximizing the value of this infrastructure has become the main driver of actions by the authorities and has predicated a mass scale assault on water connections rarely seen in the global North. How can such an event take place in America we might ask as we realise that on the streets of the world’s superpower access to basic services seem to be as fraught and contested as those cities at the other end of our developmental categories and rankings.

We live and many of us work in a world in which knowledges about cities are categorized through rankings and via the vast web of international agencies, donors and corporations, academic institutions, experts and consultants that perpetuate particular ideas about certain places. Such narrow, developmentalist ways of understanding cities has of course been written about and criticized for many years by scholars such as Jennifer Robinson. Taking these debates into account, maybe as Garth Myers has posited it’s time to rethink our ideas about what makes North and South. Detroit has often been positioned as the poster child of post-industrial decay, as the ruin porn capital of the world and a vision from the margins of our agglomerated urban future. Yet perhaps it’s time for Detroit to be disconnected from this singular view of cities and understood instead as part of many urban worlds. From such a standpoint it becomes possible to look at Detroit through the prism of African cities, rather than an embodiment of the logical endpoint of Fordism and the deindustrialization of the late 20th century.

Whilst there are many cities across Africa from which we could identify parallel situations in relation to the water disconnections taking place across Detroit perhaps the most pertinent are those of South Africa. With over 10 million people having had their utilities disconnected since the end of apartheid, hundreds of thousands left vulnerable to death, disease and the struggle to sustain everyday life in city, places such as Johannesburg may have much to offer those interested in what is happening in Detroit. Like the North American city, such programs of large scale disconnection have been predicated on the narrative of cost-recovery and the need to sustain utility companies and essential services for the metro region as authorities struggle to balance budgets and the need of the poor. Yet behind such claims both in cities such as Johannesburg and Detroit lies a more complex web of profit and usage that implicates industrial and high wealth users, racialized provision of services, privatized or privatizing utility companies driven not by concern for everyday survival but how to generate profit and municipalities that have tended to tow the neoliberal line. The huge body of research over the last decade or so that has taken place in cities like Johannesburg can of course provide some important considerations for scholars and activists in shaping how to understand Detroit’s predicament. Drawing attention to the multiple and overlapping ways in which infrastructure is governed and folded into wider neoliberalisation processes, how large scale disconnection is rationalized and legalized, the geographies of disconnection and the impacts on the urban poor have all been long established in Johannesburg and may well provide not just important areas to investigate but knowledges that may help develop quick responses to the shut off crisis.

But thinking Detroit through cities such as Johannesburg does not just need to be a exercise in futile resignation of the state of global urban infrastructure across North and South. It also asks us to think about how the South may help us to go beyond analysis of the political-economic forces at work in disconnection to actively resisting ongoing and variegated forms of neoliberal infrastructure processes such as water disconnection. Thus if we are to turn the map upside down and place Detroit in the South then there are not just these similar spatial dynamics but inspiring and courageous experiences that suggest contestation and resistance can shift the situation, can stop the shut offs and place a politics of survival at the centre of a city’s focus. As Trevor Ngange, Patrick Bond and others document across Soweto from around 2000 a range of tactics and strategies were developed by activists against the ongoing war on water access perpetuated by Suez, the French water company that had taken control of the regions water supply in a privitisation that pushed the townships to revolt against such harsh actions. In Detroit the tactics being used by a quickly evolving social movement against water disconnection have included – resisting disconnection on a house by house basis, social media campaigns, blockades of water plants, mass rallies in the downtown – all hallmarks of the mobilisations in Johannesburg from a decade ago. Running parallel to this activism a legal challenge to the shut offs in South Africa went to the Constitutional Court using Section 27(1)(a) of the South African Constitution, that ensures everyone has the right of access to water. Whilst this brought mixed success the actions should certainly inspire Detroit residents to continue to use legal mechanisms alongside the street based actions currently unfolding.

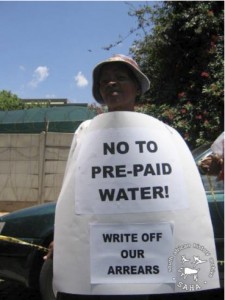

Water protest in Johannesburg 2004

Source: http://www.saha.org.za/apf/water.htm

As the water shut offs continue in Detroit finding an adequate way to understand and intervene in these infrastructural politics is pressing. Turning our attention South, to similar processes in cities such as Johannesburg over the last decade may well help us to develop explanatory frameworks, ways of understanding the motivations of various social interests and finding successful strategies to turn the tide of privitisation and disconnection.