Wangui Kimari thinks across Kenya and Brazil’s experience of raids

Lately a lot of people I know in Nairobi have been talking about raids. These that are most recent, and which have filled news broadcasts, are the terror-filled incursions by state forces in poor urban settlements which are conducted, supposedly, to fight terrorism. It seems to have been decided by state machineries that terror has a Somali face. The idea that structural factors of inhumane capitalist economics and racism catalyse the present insecurity is never considered. Instead, many communities, particularly in the east of the city, have to deal with soldier’s boots and guns on their doors, ransacked houses, disappearing and surveilled family members.

Similarly, a lot of people I know in Brazil have been talking about raids. A couple of months ago these came in the guise of state forces ensuring security for mega-events like the World Cup and Olympics. In Rio de Janeiro, while initially asserting the need to pacify communities and engender order, these raids become long term occupations which are then normalised by government politico-business speak and the support of residents from more affluent neighbourhoods.

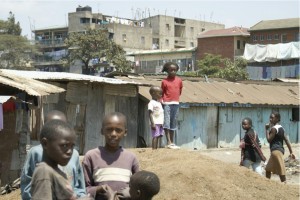

All the same it is important to recognise that the raids in these two cities are not exceptions and are rather entrenched in the more negative structural conditions that connect both Kenya and Brazil. These oppressions are anchored in the mutually shared politico-economic scaffoldings and unequal socio-natures that establish extreme income disparity, poverty, disease and exclusion, particularly for young people who constitute a significant percentage of the population of both countries. For both groups of youth, in stark contrast to the betterment that they are consistently promised in these periods of democracy and neoliberal fervour, what they face instead, before and after the raids, is huge unemployment, rising costs of living, environmental injustice and “caterpillars cutting down the pillars of houses.”[1]

In some communities like Huruma, Nairobi the entrance to the community is marked on one side by a police station and on the other by various coffin maker stalls. This spatial association may seem accidental but explicitly signals a sinister relationship which many families in poor urban settlements can attest to.

In recalling the young people who I have come across while in my 6+ years thinking about these connections between Kenya and Brazil, I remember their bold discernment of a world which has structured their fates. They know it is more than the mundane nature of urban planning that has ensured that they grew up in a palafita or a recycled mabati house next to garbage dumps and toxic industry. They know that they have stories to tell which when voiced can echo thunder and link dreams. They know that they have bulls-eyes on their backs and therefore through many powerful strategies – cultural, political, illegal, legal, contradictory, incremental – work individually and collectively to remove them.

Whether it is by starting collective economic enterprises, environmental and recycling projects and fluid and interconnected political groups and associations, young people in both locations come together to provide spaces where they can work, create and collaborate to chart new social, political, ecological and economic directions for themselves and their communities. Some initiatives such as the Ghetto Talent and Fashion show in Mathare and the Mr. and Miss Koch pageant held in Korogocho, both in the East of Nairobi, aim to engage youth on various issues such as government devolution, drug abuse and crime. Akin to the yearly Noite da Beleza Negra held by the bloco- afro Ile Aiye in Salvador, all of the above events also target the self-esteem of communities as a whole and encourage community members to remember and assert their beauty, identity (ies), community dedication and legitimacy.

It is in a bid to connect these similar experiences that I am involved in community work, research and a documentary project, the latter two sponsored by CODESRIA,that seeks to show the interconnectedness of violent structures and young people’s challenges to these conditions in poor urban settlements in both Kenya and Brazil. Inspired by the work of groups such as Reaja ou Sera Morto and Ghetto Green, we seek to discern and convey the strategies for survival (survival sharings) that youth in both locations would want to express to their peers throughout the Global South. In a time of neoliberalism-exacerbated precarity, raids and illusory democracy gospels these sharings become ever more salient.

Whether through phenomena such as BRICS, climate-change or global (lising) culture(s), generations of youth throughout the South are increasingly responsible for each other’s futures. It is important for me that we build upon and connect the work that many young favela community members and allies in both countries have been doing, working locally but also recognising the global reach of their oppressions. Their powerful work, sometimes slow, contradictory and never painless succeeds to, at the very least, negotiate the scaffoldings of violent inequality that are so pervasive in poor urban settlements. And in these many inspiring ways they teach us to recognise, connect and resist transnational structures that are connected to, but also go beyond the favela raids in both Kenya and Brazil.

While engaging in the structural comparisons that would get me to connect these two countries, during my last visit to Salvador, Bahia in 2010 I recognised, for example, that the community of Nordeste de Amarelina is Huruma in Nairobi. And that Joel da Conceiçao Castro and Amarildo are the many sons, brothers and husbands of many women I met while participating in various community organising activities in Nairobi. In light of these shared structural conditions that go beyond the current raids, it is my hope that the work we are inspired to do by youth in both locations will go a long way to ensure that in the near future it is resistance(s) and transnational favela solidarity work that will more strongly connect the youth in both Kenya and Brazil. Furthermore, that their efforts may offer situated examples of progressive practice and power from which to share and shape the (hopeful) futures of youth worldwide.

[1] A line from a poem by the young Kenyan spoken word artist TearDrops.