Emmanuel Awohouedji, a Benin environmentalist and educator, shares his experience of building and teaching a curriculum focusing on environmental problems and issues for middle and high schools in the Republic of Benin. This type of teaching is missing in Benin and requires overcoming administrative, structural and material hurdles—but also provides rich experiences for others to learn from.

My pedagogical work in the Republic of Benin refers to the planning and implementing of a comprehensive environmental education curriculum that can help young students understand and have a growing interest in—and impact on—their surrounding environments.

For the last two years I have developed this curriculum and while much is left to do, it is clear that this curriculum is missing in Benin today. Despite efforts in the early 2000s to implement environmental education, today none of the seven subjects taught in secondary classes or the nine taught in high school have a serious focus on environmental issues. Considering however the changes affecting the Beninese environment, the impacts of environmental issues, climate impact on water, food, energy, health, ecosystems, various sources of pollution (Boko, Kosmowski and Vissin n.d.), and the legislation related to environmental protection, this form of environmental education is relevant.

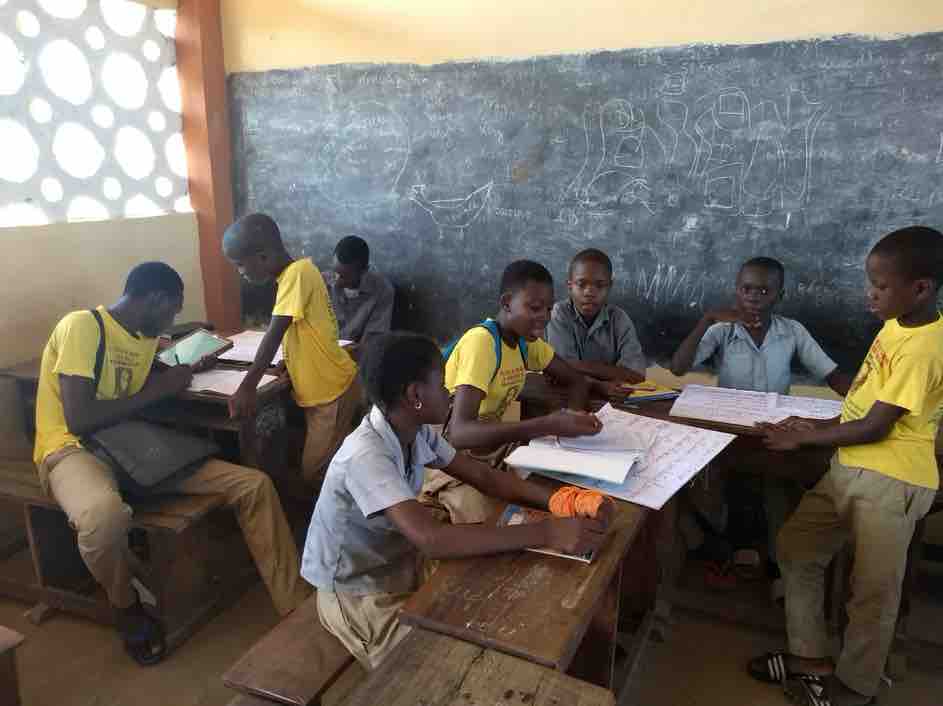

Through working with my students I have started to develop an environmental curriculum for middle and high school students in my country. Overall, I have worked with four classes, for two years, each having between 17 to 24 students and about 70 students in total. In this blog post I share from my experience in the hope that it can help others that are thinking of doing something similar and generate interest beyond Benin and Africa.

Rise and fall of environmental education in Benin

Benin has had a period of country-wide interest in environmental education, which faded away. In 1999 a series of toxic waste trade and dumping in Benin was publicly revealed, which included African and European and North American countries (Short, 2016; Inyang, 1997; Agbor, 2016). This was soon after followed by an environmental protection law that was voted on and promulgated in parliament. Later in the 2000s, the first formal initiative for environmental education was taken by the Ministry in Charge of the Environment, Habitat and Urbanism (Ministère de l’Environnement de l’Habitat et de l’Urbanisme, MEHU), which linked up with the Beninese Agency for the Environment that proposed an environmental education program for primary schools. This would aim to reinforce students’ knowledge and awareness of environmental issues and ignite a desire in them to find solutions to environmental issues in their own country and the world.

This program succeeded in creating a curricula geared at implementation throughout the six years of primary school. However, it did not last long in most pilot schools and the initiative soon faded out. The only other classes that take some environmental issues into account, for example biology, physics, and history-geography classes, don’t have any in-depth focus on environmental issues. To complement what is already taught, I set out to develop a new environmental curriculum.

Building a new environmental education curriculum

To build a new environmental curriculum in Benin it is crucial to tie it to a former rope of ancient traditions of environmental knowledge. Most African countries have built their knowledge of the world on observation of nature and nature worshiping (Chukwunonyelum, Chukwuelobe and Ome 2013). People have been inspired by their surrounding world, while finding a place within it, a cultural-biophysical process that has informed their habits, practices, and customs. People have also inscribed religious value into environmental components, which can be viewed as an important base for environmental knowledge and learning. For instance, there is a long history of sacred forests (Zinsou, 2016), which includes the living beings inhabiting them (Chouinard and Dovonou-Vinagbè 2009). Plants and roots have been acknowledged to have various important medicinal values and these living things thus form a center of knowledge, easily accessible to some, but only taught to a selected few. Overall, this means that environmental education is not a new concept, but part of old even ancient practices and understandings.

For these reasons, I portrayed my initiative as one that is about recognizing the existence of an old rope of knowledge that can be tied to a newer and more formalized one.

Therefore, I decided to launch an environmental education program for middle and high schools. This means first presenting what I refer to as “principal environmental components” to students, which includes water, air, and land, but also waste, health, cities, and the climate. Usually, we would start each environmental component with brainstorming questions which would have the students understand the importance of these elements in relation to their own culture and personal belief.

Over the last two years I have been able to teach students about various things that are fundamental to environmental issues. This has included, for instance: water, water scarcity, water related problems and possible solutions; the climate and the underlying reasons for climate change; energy and possible renewable energy sources; biodiversity and the complexity of the environment; and food chains and how pollution ends up in vital food chains that effect humans and animals. More topics will be introduced, including household waste management, cities, and air pollution.

One important vehicle to introduce and develop the program has been to organize field trips and practical activities with the students. We have been able, despite scarce resources, to organize one field trip as well as taking advantage of two other trips. The first trip was to Ouidah, a historical city about an hour and a half form the school by bus. I took advantage of that opportunity to discuss mangroves, wetlands, ocean, and sea water. Djègbadji and the area surroundings Ouidah are places that many people would know as salt making areas, but not places with big environmental benefits. The second trip was to the botanical garden of the University of Abomey-Calavi (UAC), also known as CenPreBAf (Centre Pilote Régional de la Biodiversité Africaine: Regional Pilot Center for African Biodiversity), founded by the first rector and dean of the university, Pr. Édouard Adjanohoun in 1970. The garden is comprised of 15 hectares of three categories of plants and of animals. Thanks to this visit, 44 students were able to ask questions, discover new forms of biodiversity and observe a rather well-maintained environment, which nurtured dicussions how formal and traditional knowledges relate to each other. The third and last field trip allowed us to visit the Jardin des plantes et de la nature (JNP), the National Botanical Garden in Porto-Novo the lies in the capital of Benin. This is a larger garden that offered a wider variety of species to learn about. During this visit, we had about 55 students who could learn about the importance of trees and their conservation. As a last trip for the year, we made plans to visit Sô-Ava, a wetland area with a lake village.

Challenges and a potential road ahead

The first year of developing this environmental education project was quite rough. It was necessary to gather information from various sources of knowledge, and to transform them into understandable content for the students depending on their class level. However, my expectations for teaching these classes have progressively been met. Nonetheless, some challenges remained during the second year.

Even though I am working for a private school, students face difficulties in having adequate materials for other mandatory classes, so the environmental education class is no exception. There is a lack of materials to run some of the experiments. The field trips have demanded resources such as bus rentals, catering, entrance fees (occasionally), and other miscellaneous items. Access to books is a problem. The school’s small library lacks resources and only some students are able to ask their parents for internet access and online materials. Some students have phones, but most of them are not able to pay for data and there is generally a lack of skills in using computers and electronic equipment. This means paper resources and physical materials are a must, but unfortunately difficult to provide at all time.

Central to the teaching experience have been to incorporate the varied cultural backgrounds that the students represent, which sits at the heart of tying two ropes together. This is an ongoing challenging process also for me as the teacher. There are up to 40 languages in Benin and even though I can speak two languages and understand a third, I am unable to know the full range of possible cultural meanings of the topics we study. Sometimes I feel out of my depth but this is also an interesting phase of learning for me.

Another challenge, which I am sure many teachers would recognize, is to provide a curriculum while at the same time having other teaching responsibilities. This can be daunting. Teaching requires various administrative responsibilities. Initiating a new curriculum also demands constant research and personal commitment. Combining both has sometimes been exhausting. Initially, the idea was to work with some peers, but they quickly got absorbed with their own subjects and preoccupations. Ultimately, however, the next step for me is to show to others what I have accomplished so far and try to build a team of four or five people. I have been involved with an environmental education project that was partially funded by the Ambassador’s Self Help Fund 2018-2019. The team which I worked with was quite effective and if I manage to have them work in environmental education programme with me, then the results will certainly be more impactful. On my wish list is also to write or co-write a book that captures my experiences with developing this program and its philosophy of tying the old and new rope together, linking traditional and scientific understandings. The book would serves as a resource for others to launch similar environmental education activities in their schools and maybe progressively create an environmental education network serving schools and communities across the country.

Acknowledgements

I want to thank many people in developing this environmental curriculum but especially the professor of History and Geography of the Bishop Melchior of Marion Bresillac Billingual (Ecoles Bilingues Monseigneur Melchior de Marion Bresillac) Schools of Gninin, Akassato, Republic of Benin, Mr. Zouma Donatien. I also thank Dr. Henrik Ernstson at The University of Manchester for feedback on this blog post and for publishing it at the Situated UPE Commentaries section.

Works cited and more reading

Agbor, Avitus A. “The Ineffectiveness and Inadequacies of International Instruments in Combatting and Ending the Transboundary Movement of Hazardous Wastes and Environmental Degradation in Africa.” African Journal of Legal Studies 9, no. 4 (August 2016).

Boko, Michel, Frederic Kosmowski, and Expedit Vissin. Les enjeux du changement climatique au Benin. Research Paper, Konrad Adenauer Stiftung, Cotonou: Konrad Adenauer Stiftung, n.d.

Chouinard, Omer, and Pricette Dovonou-Vinagbè. “Gestion communautaire des ressources naturelles au Bénin (Afrique de l’Ouest) : le cas de la vallée du Sitatunga.” Études caribéennes, April 2009: http://journals.openedition.org/etudescaribeennes/3630.

Chukwunonyelum, A., M. Chukwuelobe, and E. Ome. “Philosophy, Religion and the Environment in Africa: The Challenge of Human Value Education and Sustainability.” Open Journal of Social Sciences 1, no. 6 (November 2013): 62-72.

Environment, UN. Global environment outlook. Summary for policy makers, Nairobi: Cambridge press, 2019.

Inyang, Ini George. “The political economy of international trade in hazardous and toxic wastes in West Africa:theoretical and case study.” ETD Collection for AUC Robert W. Woodruff Library, 12-1-1997: 225.

Short, Rebecca. There Is No Land For Toxic Dumping In Africa. Spring 2016. http://afjn.org/there-is-no-land-for-toxic-dumping-in-africa/ (accessed April 29, 2019).

Zinsou, Marie-Valerie. “Au Benin les religions mobilisées pour la protection de la nature.” La Croix Africa, 23 December 2016: https://africa.la-croix.com/benin-religions-mobilisees-protection-de-nature/.